By Chris Heath

Photographs by Mark Seliger

January 22 1998

|

Fiona - The Caged Bird Sings By Chris Heath Photographs by Mark Seliger January 22 1998 |

"We should try to make a collage, OK?" Fiona

Apple suggests as she sits on the floor of a New York hotel room. Last

night's effort, painted and pasted onto the newspaper sports section, says,

In the case of a shorter girl studying the words that fill longer days.

We look through magazines for phrases to use, to distort. I

half-heartedly offer a New York Times editorial headline: November Darkness,

November Light. She picks up her scissors and snips free the word

ember. After that, I leave her to it. She collects suitable

words all the time. She keeps spare words on the tour bus, in the food

drawer.

Her parents - Brandon Maggart and Diane McAfee

- met when they performed together in the same musical. They had two

children, but never married. They split up when Fiona was 4. For

a while, mother and children ended up in a basement on 162nd street in Manhattan.

It was weird there. When they arrived, in the kitchen was a Kermit

doll crucified on the wall. Underneath Kermit were the words Fuck

Jesus.

From a letter to her fans, posted on her officail

Web site, explaining her MTV Video Music Awards Best New Artist acceptance

speech: When I won, I felt like a sellout. I felt that I deserved

recognition but the recognition I was getting was for the wrong reasons.

I felt that now, in the blink of an eye, all of those people who didn't

give a fuck who I was, or what I thought, were now all at once just humoring,

appeasing me, and not because of my talent, but instead because of the fact

that somehow, with the help of my record company, and my makeup artist, my

stylist and my press, I had successfully created the illusion that I was

perfect and pretty and rich, and therefore living a higher quality life....

I'd saved myself from misfit status, but I'd betrayed my own kind by

becoming a paper doll in order to be accepted.

I watch her perform in Boston. She plays

her entire album and three covers - Jimmy Cliff's "Sitting in Limbo," Bill

Withers' "Use Me" and Jimi Hendrix's "Angel." She talks to the audience

in a manic, cheery manner - like a slightly nervous ringleader pupil trying

to tell the class something important before the teacher walks in. She's

funny, too. A long-haired woman rushes up to the stage and hands her

a gift. Fiona holds it up for the rest of the audience to see. It's

an apple. She pretends to ponder this offering for a moment, then says,

deadpan, "I don't get it."

When Fiona Apple was young, and she felt like

wallowing, the song she put on was Madonna's "Live to Tell." As it played,

she would do what she calls floor-dancing: dancing while lying on the floor.

She never really felt that she could dance standing up. When she felt

happier, she would play Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone." She would

put on her roller skates. She had this ritual that she was convinced

would make her safe. She would roller-skate around the dining-room

table 88 times, 88 being the bumber of keys on the piano. After she'd

done that, she knew she'd be safe until everyone got home.

Fiona Apple is on the 34th floor of MTV's

New York offices, talking to a camera about her year. "You feel like

it's been a second," she says, sitting down, "and you feel like it's been

12 years."

When she was 12, on the day before Thanksgiving,

Fiona Apple was raped outside her mother's apartmment. She had walked

home from school, and she figures the man must have followed her. At

her building she was looking for her keys and she saw this man buzzing the

buzzer, then walking outside. It seemed suspicious, so she waited until

he was outside again, then ran in. He caught the door behind her.

But he didn't do anything. Not yet. When she caught the

elevator, she could hear him going up the stairs, stopping at each floor.

That worried her.

We fly to Las Vegas. She is bleary and

wearing her tour manager's sunglasses. Perhaps this is because she

was up most of the night drinking Surfers on Acid (some malignant combination

of Malibu, Jaegermeister and pineapple juice) with Boogie Nights director

Paul Thomas Anderson. We talk a little. She tells me about teenage

high jinks. Shoplifting underwear by walking out of the stores wearing

seven bras. Cutting 253 classes in a year. The time when she nearly

got the lead in the fourth Karate Kid movie. "It would have

been a disaster," she says.

From a quote by Martha Graham, about artistic

expression, that Fiona Apple carries around with her: No artist is pleased.

There is no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only

a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching

and makes us more alive than the others.

In my hotel room in Las Vegas, I ask her whether

she has heard this Janeane Garafalo sketch from Denis Leary's new album,

Lock 'N Load.

A few days later, I track down Janeane Garofalo.

"Oh," she says. "OK. All I can say is, yep, I did it. I

have to take full responsibility, but in the end I'm not pleased that a young

woman's feelings were hurt by it." She recorded it almost immediately

after the awards: "It was one of those deals where you don't think about

it." She says that the "lean" stuff was "just my own jealousy and envy,"

and that she actually likes Apple's record, lyrics included. "That's

just me being a dick," she says. But she totally denies that she avoided

Apple, or had a problem with her, the day after the awards: She says she

was looking after a dog and a 5-year-old kid. "Denis and I were just

screwing around," she says. "In 13 years of doing stand-up, I have discovered

time and time again, people get hurt a lot when you think you're just doing

comedy."

Fiona Apple has curious, intense faith in

the truth. In her music, she believes that if she is honest, what she

creates cannot be without worth. In her life, she believes truth is

the safest refuge. These are dangerous, high-risk beliefs.

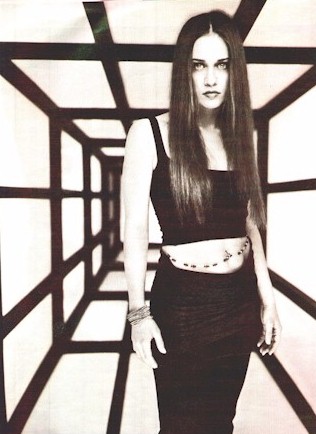

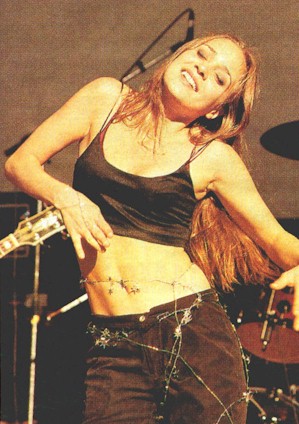

There is a rectangular tattoo at the center

of Fiona Apple's lower back. The upper half says kin, the word David

Blaine and she use to describe their relationship. Below, it says FHW.

There were two phrases that Fiona would write everywhere at school.

One was To Be Free. The other - FHW - was Fiona Has Wings.

If you see anything wrong on this page, or have any comments, or any informatin

about Fiona or her releases, her music, that you're willing to volunteer,

please email me... ThisVoice@excite.com

When Fiona Apple pulls into a new town - some place where

she has never been before but where tonight there is a theatre with her name

on, and an audience waiting to suck in her pushy, poignant songs of disaffection

and self-reliance - she takes a peculiar pleasure in picking up a copy of

the local newspaper and reading its short, skewed, action-packed summary

of her life and credentials. "Fiona, who said something bad at the MTV awards,"

she offers, by way of example, "who was in therapy as a child, who was ugly

but now is pretty..."

When Fiona Apple pulls into a new town - some place where

she has never been before but where tonight there is a theatre with her name

on, and an audience waiting to suck in her pushy, poignant songs of disaffection

and self-reliance - she takes a peculiar pleasure in picking up a copy of

the local newspaper and reading its short, skewed, action-packed summary

of her life and credentials. "Fiona, who said something bad at the MTV awards,"

she offers, by way of example, "who was in therapy as a child, who was ugly

but now is pretty..."

Something like that. Maybe more: Fiona, who

has sold 2 million copies of her "Tidal" album, whose "Criminal" video shows

her flouncing in her underwear, who told the MTV audience, "This world is

bullshit," who was raped at the age of 12, who is crazy keen about Maya Angelou,

who was discovered when a freind of hers baby-sat for a music publicist

and passed on a tape, who told a magazine, "I'm going to do good things,

help people, and then I'm going to die," who is too thin, whose parents split

up when she was young, who never smiles, who is only 20 and dates magician

David Blaine, whose life was ruined when they started calling her "Dog" at

school...

Much of this is true. Some is sort of true.

Some is false. But in the busy, greedy, impatient '90s, we become whatever

may be written about us in one or two perky paragraphs, and hers might lead

one to believe that Fiona Apple is either a precocious, calculating prodige

or an unbalanced, ungrateful freak. That is the great sucker punch

of modern celebrity: It draws in the Fiona Apples of this world with that

most wonderful of all promises - to be understood - and yet humans are still

to invent a quicker, more-efficient method of being misunderstood by the

greatest possible number of people than becoming famous in America. Fiona

Apple has been discovering this for herself.

As she collages, she mentions how ludicrous some

of the attention she recieves is, and for some reason we try to work out

the appropriate mathematical equations that explain this.

Me: Uninteresting plus famous

equals interesting.

Fiona Apple: [Nodding] Or Normal

plus famous equals special.

When I arrived, at 4 in the afternoon, Fiona

Apple answered the door in a white bathrobe. She had just woken up.

Now dressed, she sits on the floor, on the quilt from the bed next

door that has been laid out over the carpet, exactly parallel to the walls,

neatly folded back where it meets the couch. Two candles have been

carefully placed at either end of a diagnal across the room. She is

particular about these things. Often she has to change hotel rooms

because the rug is the wrong color, or the bed is too close to the door and

she'll feel as though someone might come in and suffocate her. "I've

been sick for two months," she explains. "There's a lot going on in

my head; there's a lot going on in my personal life; there's a lot going

on everywhere." And she will do whatever she needs to do to cope: "I

am going to fucking put my candles where I want, and I am going to make my

dumb collages."

The radio is tuned to a hip-hop station. She

does not travel with music and says that she bought only one new CD in 1997:

Wu-Tang Forever. There is no TV. "I decided that TV was

evil," she explains with a smile. And she was worried that she was relying

on her standard method of getting to sleep in hotels: "Get stoned and watch

TV." So she asked the hotel to have the TVs physically removed.

Me: Demanding request plus famous

equals It'd be a pleasure.

Fiona Apple: Exactly. [Laughs] Or

it could also equal you fucking egotistical patronizing bitch.

Third grade was best, because of Miss Kunhardt,

who had been to the Galapagos Islands. "She was like Indiana Jones as a woman,"

says Fiona. "I remember just being so excited in the morning." Things got

bad in fifth grade. Fiona was leaving chapel one morning, walking down

the staircase with her freind, and she said, "I am going to killmyself, and

I'm going to bring my sister with me." She was taken to the principal's

office, and sent for psychiatric evaluation. She had also been refusing

to go to school. They said she was showing signs of depression. The

therapist did ink-blot tests and they told Fiona that she thought too much.

(Hardly, one would suspect, a diagnosis that would do anything but exacerbate

the very problem it identified.)

There was already music. There is a video

of Fiona at 7 or 8 playing at a piano recital. You can hear a vioce

say, "Fiona's coming up next...and this is not a typo! She did write

this herself!" It was a piece called "The Velvet Waltz." ("Oh, my God,

she now says. "It sounds like some kind of gay porn.") she would spend each

summer in California with her father. He remembers suggesting, when

she was about 9, that they write a song together. She wasn't interested.

"I guess," he says, "she wanted to do it on her own. The next

summer she came back - she had trouble sleeping at night and she had written

these inaccessible lyrics about darkness. It kind of scared me in the

beginning." She was just another talented, slightly messed-up young

girl, one who liked socks that didn't match, clothes without seams and her

glass-animal collection.

There is a moment that has always stuck in her

father's mind, when Fiona was maybe around 8. His freinds were round

the house for fight night, and they were reminiscing about terrible things

that had happened to each of them. And they were laughing about it

all, as adults do when they look back over the canyon of their past tragedies.

Fiona was listening. And - how many reasons would Mr. Maggart

have to remember these next words - Fiona said, with disappointment, "Nothing's

ever happened to me."

It would.

She really hadn't expected to win. She

thought it would be Hanson. When they read out her name, it all began

to percolate in her head...she was a little bit drunk...she had just been

having an argument...and it felt like she was becoming head cheerleader after

years of watching the cheerleaders from a distance...and suddenly she was

onstage and actually saying what was on her mind....I didn't prepare a

speech and I'm sorry, but I'm glad that I didn't, because I'm not going to

do this like everybody else does it.... You see, Maya Angelou said that we,

we as human beings at our best can only create opportunities and I'm going

to use this opportunity the way that I wanna use it.... So what I wanna say

is, everybody out there that's watching, everybody that's watching this world,

this world is bullshit and you shouldn't model your life about what you think

that we think is cool and what we're wearing and what we're saying and

everything. Go with yourself.... And it's just stupid that I'm in this

world, but you're all very cool to me....

It was a defining moment. "I went,"

she later commented, "from being 'tragic waif ethereal victim' to being 'brat

bitch loose cannon.' " These things happen. "To anyone that knows

me," she says, "I just had something on my mind and I just said it. And

that's really the foreshadowing of my entire career and my entire life.

When I have something to say, I'll say it."

Fiona Apple fetches some food from her hotel minibar.

Her favorite: un-turkey sandwiches. "I have, like, 17,000 of

them," she says. Apple is a vegan. On tour, she eats the same thing

every day before a show: split-pea soup.

Fiona Apple fetches some food from her hotel minibar.

Her favorite: un-turkey sandwiches. "I have, like, 17,000 of

them," she says. Apple is a vegan. On tour, she eats the same thing

every day before a show: split-pea soup.

She empties the contens of her bag

("What my freind Michelle calls the Black Hole") onto the quilt. I

request an inventory. "A bag of jewels and

ribbons...makeup...lighters...matches...rolling papers...a photo album..."

-this she picked up from home: faded pictures of her and her sister playing

as kids - "lots of empty card packets from when David was around...lots of

hotel bills...the Jenny McCarthy book - I like her...a tin of makeup someone

got me...a book of poetry about death..." - a friend suffered a loss and

she wanted to understand - "my psychiatric medication..."

For what?

"My psychiatric problem," she answers

succinctly.

Have you been on something for a long time?

"A few years. I don't get depressed for

a long time. What would happen to me is the most exhausting thing.

I wanted to die before. I truly did want to die before. I

remember I would be sitting in my shrink's office, looking at his computer

with on of those screen savers on, and they have all these cubes in different

colors, and I swear my mood would change....A purple square would come up

and I'd feel, 'Everything's OK,' then a green one would come up and I'd be

'Everything's terrible.' It would make no sense to me. I still

don't understand it.

Finally, there's her journal. I ask her

to open it at random and read me something. It's a few lines of verse.

Maybe a lyric-to-be.

People don't like you, honey, that's a good

sign

Most people don't know nothing but opinions

Very few find the facts

You keep trying to make them all side

with you

You're gonna waste all your time

Because you can't get 'em, shouldn't want'em,

don't need 'em, so move on, be righteouse and relax

"That's me writing to myself," she says.

"I'm very thrilled that other people can get something out of my songs,

but I write them for myself."

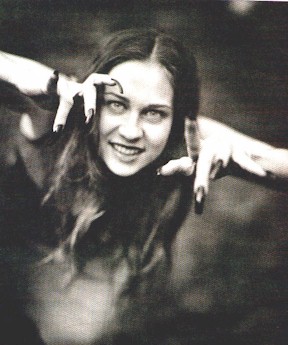

As we speak, she contorts her body intoa

little ball, or sticks limbs out at the unusual angles available only

to the double-jointed. When she talks, she talks boldly, but sometimes

she goes silent. She stares ahead, or down, and for a while she just

doesn't say anything.

One of the subjects she keeps referring to onstage

tonight is the boyfriend about whom she wrote some of Tidal's more

barbed songs. She tells the audience that she recently spoke with him

for the first time since they broke up, and how good she feels because she

doesn't hate him anymore. His name is Tyson. She tracked him

down at his college one morning after she'd been up all night and had ended

up drunk and alone and wanting someone to talk to. They told her he

was sleeping. "Tell him it's Fiona," she said. They talked for

three hours.

Still, I am a little surprised a few days later

when she passes on his number for me to call him at college in Atlanta, where

he stufies bio and moonlights as an acid-jazz DJ. He tells me about

how they got together, a year after they first met, when he was out rollerblading

on the Columbia Universtity campus. "After that day," he says, "we

hung out with each other for 10 days straight without going home." They

went out for two and a half years, on and off. He was her first real

boyfriend. Then it ended. "I remember it being all my fault,"

he says. "Well, 95 percent my fault. I started seeing this other girl

and likng her a little bit. And she said one day, 'I never want to

see you again.' And then a year later the album's out." (Later,

Fiona tells me that afterward she became friends with the other girl. One

night they tried ecstacy together and were kissing. They were going

to take a photo and send it to Tyson. "We thought, 'This'll be the

greatest,' " she laughs. " 'The two girls that he fucked over. Let's

make him think that we're together now.' ")

Tyson remembers listening to Tidal for

the first time. He knew he was in there, adn he would go through the

songs, over and over, figuring it out. " 'Sleep to Dream,' pretty much

felt like that's what she was saying to me the last time I talked to

her," he says. "And the video was set up in a way so it looks like her bedroom

- a futon on the floor, a TV." The first time he saw that video, he was on

his bed at college, lying on his back, with a girl on top of him, kissing

his neck. And suddenly he saw Fiona. "Kneeling on the ground,

looking through the TV, looking straight at me," he says. Saying those

words. This mind, this body and this voice cannot be stifled by

your deviant ways/So don't forget what I told you, don't come around, I got

my own hell to raise.

He had to ask that girl to get off him. He

couldn't carry on.

She's frank to a fault. "Alanis broke

the ceiling, and then I walked into an office and they said,

'Girl...young...songwriter...sign here.' " And she's nicely sarcastic.

After talking about her acquaintance with Marilyn Manson, she says,

"Oh, it's just an act, I like to act angry....Me and Manson got together,

he said, 'I'm going to act like a Satanist and you act like a brat, and everyone

will pay attention to us and then we'll both say we're misunderstood and

then we'll run off the edge of the earth.' "

After about an hour, she is done. "One

thing," the MTV interviewer asks, "before you go. Do you have any favorite

or worst Thanksgiving experiences?"

Fiona's brow furrows, and then she looks up at

her sister, Amber, who is sitting just off-camera, and the two of them start

laughing.

"You can't answer that," says Amber. "That's

not a good question."

"We don't want to..." says Fiona, and the two

of them laugh some more, the almost hysterical merriment of a sisterly

secret.

"When they find out," Fiona says to Amber, "it's

going to be really bad that we're sitting here giggling...."

There were three locks to open to get into the

apartment. She was on the third lock when he started down the hallway

toward her. Later she would remember, somewhere in her head, a weird,

off-kiler thought: It's Jimi Hendrix. maybe she was trying to imagine

she was off in some strange fantasyland. The man who was not Jimi Hendrix

came closer. She said she didn't have any money. He said he didn't

want money. He had some kind of screwdriver or tool knife, and he told

her that if she screamed, he'd kill her. She remembers letting out

a sigh, and her muscles falling.

On the other side of the door, Fiona's dog was

barking and growling. Maybe the dog saved her life. Otherwise,

the two of them would have gone into her apartment, and...who knows?

When he had finished - maybe 10 minutes - he

said something to her: "Happy Thanksgiving. Next time don't let strangers

in." After he left, she opened the third lock and went into the apartment.

Her sister and her mother were holiday-season shoe-shoppingin midtown.

She phoned for help, and waited. All this time she was paranoid

that there was also someone in the house. She started checking all

the closets. She would continue to check them for years.

When she gave her statement to the police - she

had to retell it in all it's specific ghastliness, over and over again -

she was left in a room. On the table was a notebook detailing past

cases. She says that her only true regret of this whole period was

opening up that book and looking inside: the most horrible things,

beyond imagination, all in a day's work. A baby being molested.

Stuff like that.

She still has terrible, violent dreams. The

same feelings, but with different people. Sometimes people she knows.

For years, older men would make her nervous. Even when she made

her album, she refused to sit next to any of the musicians or Andy Slater,

her producer and manager. She's honest enough to make other connections:

"I had really bad boyfreinds for a lot of times that had slight physical

resemblances to the man that raped me."

Fiona hadn't thought about whether she was going

to talk about her rape in public until the day a journalist asked her abour

the song "Sullen Girl." He wanted to know if it was about a guy leaving her.

And it is not. It's lyrics - "They don't know I used to sail

the deep and tranquil sea/ But he washed me shore and he took my pearl/ And

left an empty shell of me" - are in part about what happened to her. So

she said so. "I thought that ultimately, no matter what happens, if

I lie about this, I don't like what that says," she explains. From

then on, interviewers would agonizingly, circuitiously bring up the subject.

"I'd be, 'You want to ask about when I was raped?' " she laughs. "I

was, 'please don't act like I have got food in my teeth. It's out in

the open. It's not something that I'm embarassed about, so don't act like

it's something that I should be embarassed about.' Which I think I

was sensitive about, because I was embarassed about it for a long time."

How different do you think what you do now might

be if none of this had happened?

"It's funny, because I don't think that maybe

I would be here. but then again, I don't think I would need to be

here."

Explain what you mean.

"I want everyone to understand me. I want

to be friends with everybody. I want everybody to know how I feel,

and I want them all to respect it and to think that it's OK. And that's

why I'm sitting here....I think it was my desperation that drove me to have

the will to do it."

There is a closet in Fiona's bedroom at her mother's

apartment. If you look closely you will see the splits where Fiona

has stabbed it repeatedly with her stepfather's Boy Scout knife. That

is what she used to do when she got mad. "It's better," she points

out, "than stabbing someone." At the bottom is a single word that she carved

one time, kneeling down there, crying. The word is strong.

Andy Slater plays me three versions of "Sleep

to Dream" to help me understand how Apple's music ended up as it is on

Tidal. On the first, mostly piano and voice, she holds the song

together with a manic, percussive, awkward left-hand piano rumble: clever,

but unlovely. In it's second version, the studio musicians turn the

song into a silly, New Wave eccentricity, with lots of asymetrical guitar

in the verses and a horrible, choppy rock chorus. Fiona Apple sings

over the top like a fake punk rocker trying to catch up with something.

The third is the stark, sinuous, final version. That was Slater's job:

to try to work out how she needed this music to sound. One day he took

her to a record shop to see where she was coming from. She bought the Roots,

the Pharcyde, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald and Marvin Gaye, which helped

him a little.

That is one story of how Fiona Apple's album

was made. It is not the only story. Those months in Los Angeles

were not good ones for her. She was in a rough way. For one thing,

she was anxious around the musicians. "I just assumed that he had payed everyone

off to be there and that they were all really pissed off to have to be there

with me," she says, "because I was a stupid little kid and they were real

musicians." Also, things weren't great with her parents. And

there were deeper problems. She was getting thinner.

She had strange eating habits. "It was

colors," she explains. "I couldn't eat things that looked a certain

way, that were a certain color. I mean, there was a time when I couldn't

eat things that I felt clashed with what I was wearing. I don't mean

clash like 'fashionably clash' - there was just something in my head that

if it didn't balance, I couldn't eat it, and I was so afraid of doing the

wrong thing, I felt like I was doing it because 'I don't want to be crazy.'

'I'm going to eat that fucking apple right now, even though I'm wearing a

yellow dress.' This would go on in my head all the time. And

it's exhausting. I would tell my sister, 'I'm just so tired I can't

manage anymore.' I felt like I was the mother of some retarded child

that was throwing fits all the time, and I couldn't help it. It would

take me half an hour to pick an apple out of the drawer. I couldn't

pick the right one."

So why were you like that?

"Because I felt like I had no control over

my life, and that was the only way for me to take control over my life."

She had a problem, but she didn't like it being

misunderstood. "I definately did have an eating disorder. What

was really frustrating for me was that everyone thought I was anorexic, and

I wasn't. I was just really depressed and self-loathing." The

distinction was important to her. "For me, it wasn't about getting

thin, it was about getting rid of the bait that was attached to my

body. A lot of it came from the self-loathing that came from being

raped at the point of developing my voluptuosness," she explains. "I

just thought that if you had a body and if you had anything on you that could

be grabbed, it would be grabbed. So I did purposely get rid of it."

Slater was worried, and unsure what to do. He

felt that, whatever these problems, if she didn't complete the record it

would be worse for her in the long run. But, eventually, he pulled

the recording to a temporary halt. Steps were taken. She got

back into therapy, and some improvement was noted.

As she talks about this, Fiona pauses. She

starts a sentence, then stops it. There's something she's not sure

about telling me. But Fiona Apple can never withstand the temptation

of the truth, so she explains. As much as any professional help, it

was a new friend who pulled her out of the darkness. That friend was

Lenny Kravitz. "I wasn't his girlfriend or anything like that," she

says. But Kravitz and a friend came to the studio one night and told

her how good it sounded, and they were the first people she believed.

"And," she says, "I ended up talking to Lenny a lot. He was the

first person I could sit next to. Literally...he'll never understand

how much he helped me." When he went off on tour, they would speak

all the time. If you look at the video for Lenny Kravitz's "Can't Get

You Off My Mind," where he is filmed talking on the phone, it is Fiona Apple

on the other end of the line.

Soon she had an album, but not a name. Or,

rather, she had too many names. When I sit with Andy Slater, I

see one old demo tape marked with the name Fiona Apple McAfee-Maggart.

Apple, her middle name, was from her father's grandmother. When she

met the people from the record company, she had only one stipulation: "I

said, 'Not Apple.' " She thought of finding another name altogether;

after all, that's what Maya Angelou (real name: Marguerite Johnson) did.

Fiona's mother chipped in with a suggestion: "She phoned up and said,

'I've got a great name! You know how you're always alone? You

could call yourself Fiona Lone.' " The one idea Fiona considered seriously

was Fiona Maria. "Then six months later," she says, "the contract comes

- 'Your stage name is Fiona Apple' - and I started laughing." The biblical

resonances didn't strike her until much later on. The apple: the thing

that starts all the knowledge, but that also starts all the trouble.

A few times, she protests that she feels fine.

She sinks back into her seat. "You know what?" she says slowly.

"I really feel like shit." And we laugh. Though it's hard

to guess from many of the words that get quoted, most hours with Fiona Apple

are both funny and fun - time spent in the slipstream of a smart, wry 20-year-old

who finds her own life, and those that surround her, a source of constant

amusement.

When Fiona Apple read her first bad review, she began to scratch

her left wrist with her fingernails on her right hand. It was some

guy in Boston, saying that she was Sony's answer to Alanis Morisette, that

she had a lot to learn and that she was saved by the instrumentation.

(He also said she was "precocious." She somehow misunderstood and thought

he said "pretentious," which made it worse.)

When Fiona Apple read her first bad review, she began to scratch

her left wrist with her fingernails on her right hand. It was some

guy in Boston, saying that she was Sony's answer to Alanis Morisette, that

she had a lot to learn and that she was saved by the instrumentation.

(He also said she was "precocious." She somehow misunderstood and thought

he said "pretentious," which made it worse.)

She scratched and she scratched, all the way

up her arm. There are still some dark patches on her wrist, where she

dug in the deepest. "I have a little bit of a problem with that,"

she says, frankly. "It's a common thing."

Yes, but it's not a great idea.

"I know. I have bad, violent dreams and

it has a bad effect on my mind. I know, it's bad. But it's not

like a hobby of mine.

Did it make you feel better when you did it?

"It just makes you feel."

Sometimes, she bites her lip as hard as she possibly

can. "And it'll be bleeding, and I can't stop, because it almost

feels so good when I bite my lip." Pause. "It was never, like,

'I am going to hurt myself and put myself in the hospital.'...It is that

I am going to give myself the pain that I need to feel to put the punctuation

on this shit that's going on inside."

How do you react when you realize people think

you're crazy?

"The first thing that happens is just the frustration

and sadness. And urgency, the 'No, no, you didn't get it.'"

Would you like them to know that you're not

crazy?

"Sure, but I'd better sane them up first, because

there's a lot of them that are crazy and that's why they think that I am....The

most annoying thing for me to hear about myself is that I'm trying to make

people have a pity party for me. Everything that I've gone through

has been dramatized by the people who've written about it, not by me. I'm

just saying, 'This happened to a lot of people.' Why should I hide

shit? Why does that give people a bad opinion of me? It's a reality.

A lot of people do it. Courtney Love pulled me aside at a party

and showed me her marks."

Does it ever worry you that you're too young

for all of this?

"Well, if I am, it's a good thing that I've got

all of this to help me grow up."

I think it worries other people.

"But what's going to happen that they're worried

about? They're worried about just the possibility of my ongoing pain,

or are they worried about the possibility of a horrible crash ending? That

guy, Tony Robbins, the motivational speaker, said something that just sounded

cheesy....He said, 'Hey, you know how risky life is? You don't get

out alive.' But in a sense, basically, what he's saying is: What the

fuck else are you going to do?"

"No. What did she say? This is

really going to make me upset, because I really like Janeane Garafalo, and

I knew that she hated me....That girl was at the MTV awards and she was giving

me a really weird vibe and really avoiding me."

I play her the track, titled "A Reading from

the book of Apple." It begins by perfectly echoing Apple's MTV speech, then

it heads off: You shouldn't model your life about what you think

that we think is cool.... Even though I have an eating disorder and

I have somehow sold out to the patriarchy in this culture that says that

lean is better. Even though I have done that, and have done a video

wherein I wear underwear so that you young girls out there can covet, and

feel bad about what you have and how thin you're not. The point is,

I have done it, I am lean. That's why I did succeed sooner than maybe

other musicians that maybe were better songwriters....I don't

know...better lyricists...better vocalists...I can't say that. But

I do know this: This world is bullsh-...did I say this world is bullshit?

'Cause it is. And my boyfriend can make you disappear. He can

pull something out of your ear and say things like, "We have not met before,

have we?" Go with yourself.

To begin with, after I click off the tape

recorder, Apple is composed: "She is absolutely right, about the video

and what it says to girls, but she's looking at my message at the beginning,

and she's not waiting for the end. Because..."

It's the she cracks. Big tears dollop down

her face. I feel awful, fetch tissues. She begins talking some

more. "Since that video was made, I've gained about 20 pounds on

purpose..." Fiona says she is currently 110 pounds, and has varied between

95 and 125 pounds - "so that people can see me like that. I know

what I'm doing. Bitch. I'm going to get bigger and bigger, and

the girls are going to see that I don't care and that I feel better like

that. Of course I have an eating disorder. Every girl in fucking

America has an eating disorder. Janeane Garofalo has an eating disorder

and that's why she's upset. Every girl has an eating disorder because

of videos like that. Exactly. Yes. But that's exactly what

the video is about. When I say, 'I've been a bad bad girl, I've been

careless with a delicate man' - well, in a way I've been careless with a

delicate audience, and I've gotten success that way, and I feel bad about

it. And that's what the song's about, and therefore, that's what the

video looks like."

Fiona talks about Courtney Love: "In a way I'm

trying to do exactly the opposite of what she's done. Start out being

lean and the absolute perfect marketing package, and slowly, I get more power,

becoming more of myself and exhibit the happiness that comes from that....

I mean, my plan is to gain enough weight that I can reall be considered

voluptuous, and do my 'First Taste' video. And I am preparing

myself for what is going to happen. because soon they will be saying that

I'm fat. And it will hurt me."

We say goodbye, but Fiona calls me a few hours

later. "First of all," she says, "I think it's good that she said that....

Because people who may have been wrongly influenced by me can be better

influenced by her for saying that. I guess. But..." It's

a big but. She's furious that Garofalo didn't say anything to her when

they were in the same room. "I wrote this little poem for her," she says.

The poem begins as a pastiche of "Shadowboxer": "Once voluptuous, now

so lean/What a pretty marketing scheme..." Then it turns on Garofalo. The

final four lines are:

Well, I best be off now to primp and preen

But before I go, here's an end to your

mean

I may be a paradox of gestures and genes

But you are a cowardly bitch,

Janeane

"I have problems," she says, "but everybody's

got problems, and I sometimes honestly have felt in my life that people have

used me as a way to make themselves feel better, because I'm a very

good subject to save. And sometimes I think: 'I'm not that bad off;

it's really you that's making me feel like shit.'"

She's been thinking about this stuff. The

first new lyric she wrote since finishing her album - for a song called "Limp"

- begins:

You want to make me sick, you want to lick

my wounds, don't you baby?

You want the badge of honor when you save

my hide

But you're the one in the way of the day

of doom, baby

If you need my shame to reclaim your

pride

It's another wise, high-risk warning, as

applicable to the world as to those around her. If she shares her troubles,

it is to normalize them, not to offer them up as public melodrama. There

is a long way to go in the Fiona Apple story. She will make more mistakes

and suffer more woes. She will make strange and brave records, though

they will not always sem to be the right kind of brave or the right kind

of strange. Maybe she'll be thin, and maybe she'll be fat, and maybe

neither of these will help make her what she wants to be. maybe she'll

realize that it's easier just to cut her hair off... and then she'll see

that that doesn't work either.

And she'll be glad, in a way, of your attention.

But, if you feel anything for Fiona Apple, think twice before adopting

her as the person you worry about.

Fiona Apple used to have this day-dream fantasy.

She will walk into school chapel and there will be these lumps beneath

her clothes, just beginning to show. She'll stride down the center

aisle and kneel in front of the altar, and all of her clothes will peel off.

Her wings will show themselves. She will look at everybody -

all those people who had teased her, or laughed at her, or talked behind

her back about how weird she was - and then she will rise up and fly out

of the building. And as she sweeps into the sky, free and triumphant,

she will hear them all whispering. Many voices, but all saying the

same three words; at last acknowledging, with their amazed chatter, what

she always knew, and they never believed.

Fiona has wings... Fiona has wings....

Fiona has...